Had the pleasure of attending two excellent concerts last week. On Thursday, Alexander Shelley and the National Arts Centre Orchestra offered a spirited rendition of two tone poems by Richard Strauss (1864-1949), Don Juan and Tod und Verklärung (Death and Transfiguration), works written when he was 24 and 25 respectively, that established Strauss’ reputation as a modernist composer.

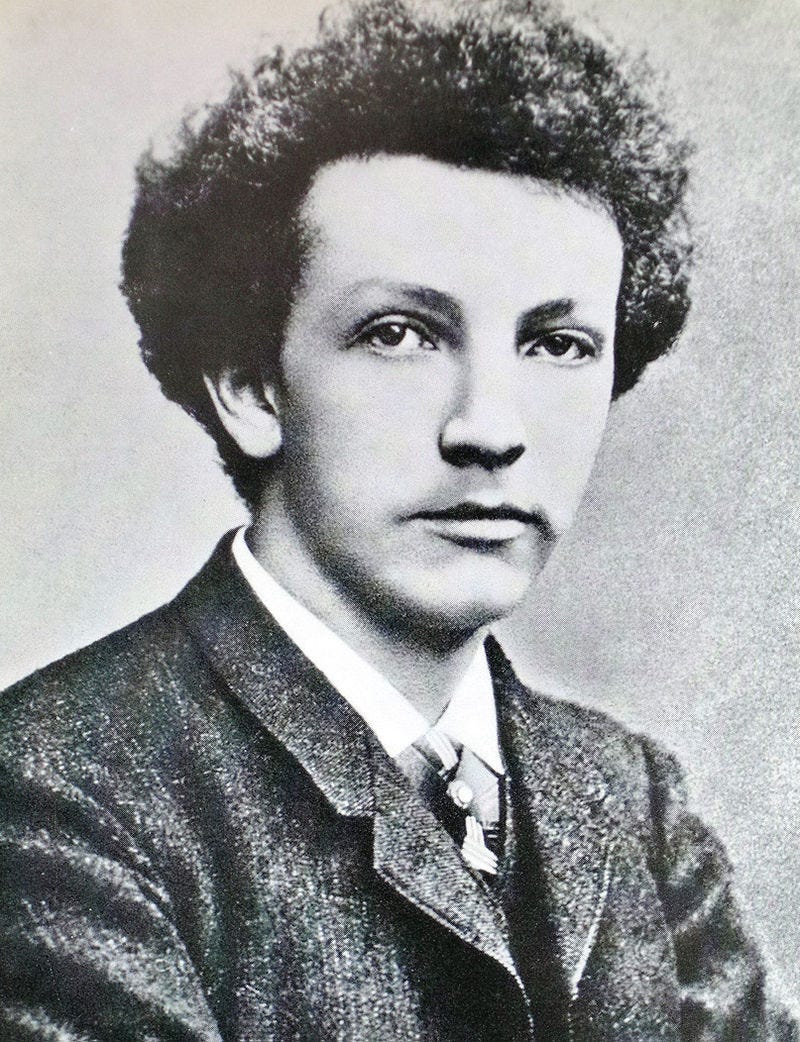

Strauss in 1888, the year he composed Don Juan. Source: Wikipedia, public domain.

In the Strauss version the Don is not so much a womanizer as a dreamer seeking the perfect woman; when he does not find her, he allows himself to be killed in a duel. (Contrast this with how Don Giovanni comes to his end in Mozart’s opera!)

(Here is a version by the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, recorded in 2020.)

Even more than Don Juan, Death and Transfiguration exploits the rich, drawn-out harmonies which would become so characteristic of Strauss’ work till the very end of his life.

Shelley and the NACO did full justice to both pieces, displaying the rich palette of sound in an ever forward-moving drive, keeping the listener engaged throughout.

Death and Transfiguration clearly means a lot for Maestro Shelley. At the start of the concert he explained its story and significance in French. Then, before the piece was played in the second half, he elaborated on it again, in English this time. Well, it must have meant a lot for Strauss himself: As he lay on his deathbed in 1949, he said to his daughter-in-law: "It's a funny thing, Alice, dying is just the way I composed it in Tod und Verklärung."

The program notes (accessible only on your phone or if you go to the trouble of printing off its 16 pages) helpfully included texts by Alexander Ritter. Strauss had asked him to compose an explanatory poem for each of the four sections.

(Several versions of Tod und Verklärung are available on the internet. Here is one from 2018 by the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France.)

Each of the two Strauss works was preceded by world premieres commissioned by NACO, the first by Kelly-Marie Murphy (b. 1964), Dark Nights, Bright Stars, Vast Universe, the second by Kevin Lau (b. 1982), The Infinite Reaches. I’m sorry to say that neither grabbed me emotionally — not a first time for a piece by Murphy, but a disappointment with Lau after having heard his exciting String Quartet No. 4 at Chamberfest this summer. (We’ll hear three trios of his in a Chamberfest concert next week.)

Wait, that’s not all! Before the intermission we watched in amazement as armless horn player Felix Klieser (b. 1991) performed Mozart’s Horn Concerto No. 4 in E-flat major, K. 495 to perfection!

Felix Klieser. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2017_Sternstunden-Gala_-_Felix_Klieser_-_by_2eight_-_DSC2987.jpg.

The whole concert was livestreamed and can be watched here: https://nac-cna.ca/en/event/35146

On Saturday we ventured deep into Hull to attend a concert by Ensemble Prisme, this region’s most underappreciated chamber group. Ensemble Prisme is a collective of musicians.

Some of the musicians of Ensemble Prisme. Ben Glossop is on the extreme left.

The concert took place in the Eglise Notre-Dame-de La-Guadeloupe (which is called Notre-Dame de l’Eau Vive by Google maps; the latter name actually refers to the paroisse which comprises three churches).

First we heard the quintet Trapèze by Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953), written in 1924. It is for oboe, clarinet, violin, viola and double bass, a combination as unusual as the music is quirky — not unexpected from this composer. Remarkable was how the double bass (John Geggie) often played a leading role.

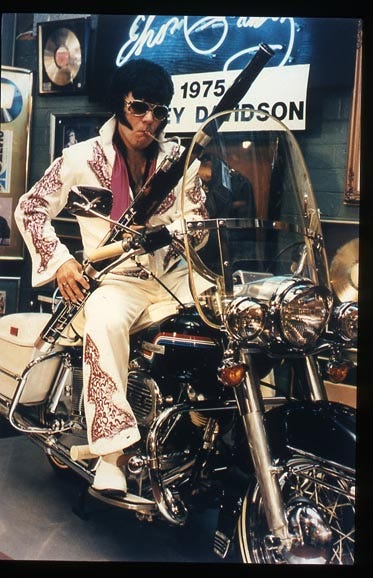

A short piece by American composer Michael Daugherty (b. 1954), Dead Elvis, followed where bassoonist Ben Glossop, always ready to ham it up, performed, white suit with high collar, sideburns and all.

Source: Daugherty’s web site.

Dead Elvis is for the same set of instruments as L’histoire du soldat by Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971), the final work on the program: clarinet, bassoon, trumpet, trombone, violin, double bass and percussion. Composed in 1917 and orginally a musical play, its instrumental version is a 9-part Faust-like story of a soldier who trades his violin with the devil in return for the secret of gaining vast amounts of money. In the end, he deliberately loses all his wealth in a card game with the devil so that he may be liberated from his richness which had not made him happy and had alientated him from his family and home village.

With the exception of one sentence of welcome spoken in English, all (extensive) oral explanations and texts projected on the wall of the church were in French. A more inclusive approach would likely enhance the profile of this excellent group of musicians.