The evolving Papacy — Ukraine’s Armaments — Bioelectricity — Daniel Kehlmann || Freedom = Choice?

June 12 Issue

Can the Church evolve?

Fintan O’Toole: When the papacy lost its role as temporal monarch in 1870, the pope “became a new kind of emperor, one who rules not over space but over time. Armed with these special powers of infallibility and immutability, he could defy history and social change.” The language of “hierarchy, subordination, obedience, immutability … made the Church a natural ally of authoritarian regimes, especially in the forms they took in Catholic countries.“ Mussolini, Franco, Pétain, Salazar… “The spiritual dictatorship of the pope provided a model for its temporal equivalents.“

In principle the imperial Church was dismantled by the Second Vatican Council, convened by Pope John XXIII in 1962. It reimagined authority in the way the secular revolutions of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries had—as derived from the people.

Two counterrevolutionary popes followed (Wojtyła/John Paul II and Ratzinger/Benedict XVI). But then came Francis. “His papacy was revolutionary, not in its content but in its conduct — the papacy is a display of manners. The pope acts out an idea of what good authority looks like.“

Alongside his religious faith, Francis placed his faith in the possibility of a form of leadership that is stripped of power, magic, and enforced obedience and that relies instead on the expression of shared respect and mutual love. But he was unable—and perhaps unwilling—to give that faith an adequate institutional form, one that truly recognizes the equality of the female half of humanity and that does not in reality continue to judge LGBTQ+ people harshly.

Leo will be a good pope if he succeeds, in his own quieter and more cerebral way, in sustaining the decency, compassion, and openness of his predecessor. He will be a great one if he manages to translate that benign comportment into the kind of change that does not ultimately depend on the personality of a pope.

Arms Race in Ukraine

Tim Judah reporting from Kyiv (datelined May 16, 2025):

Since the beginning of the Russian invasion in 2014 and especially since 2022, Ukraine’s military industry has risen like a phoenix, and if there were more money, it could produce even more weapons. In 2024, according to Herman Smetanin, the Ukrainian minister of strategic industries, the country’s military production was $35 billion—thirty-five times more than in 2022.

In February 2022 the Ukrainians had virtually no military drones. Last year they made 2.2 million, and this year they hope to make 4.5 million.

(See also my August 23 diary entry, updated September 4.)

We are electric

Tim Flannery reviews:

We Are Electric: Inside the 200-Year Hunt for Our Body’s Bioelectric Code, and What the Future Holds, by Sally Adee, Hachette, 360 pp., $30.00; $19.99 (paper)

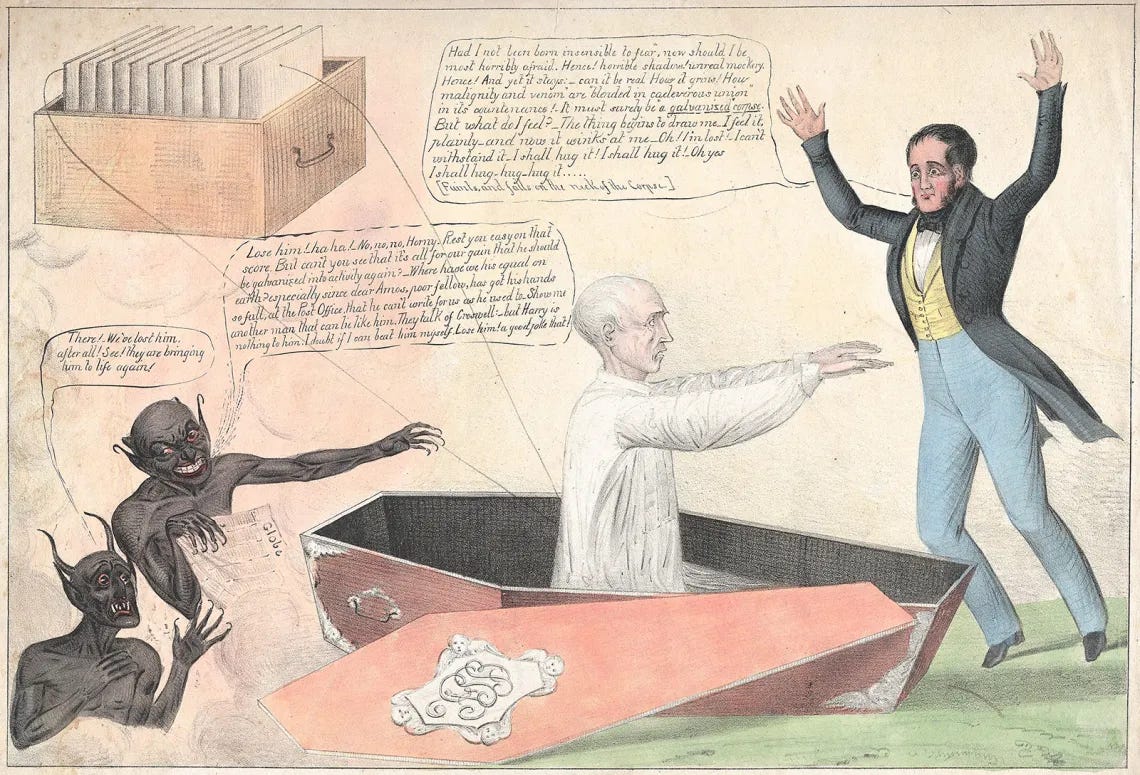

The 18th century saw much debate about how electricity is generated. Frogs were the favourite experimental subject. Emil du Bois-Reymond’s “great achievement was to directly detect the electric current that courses through frogs’ nerves.“

There is something about electromedical research into the brain that attracts the oddest people. The primary tool used to investigate this area today—the electroencephalogram—was invented in the 1920s by the German psychiatrist Hans Berger, who, according to Adee, was originally “determined to find the psychophysiological basis for mental telepathy.”

In the 1960s, … the prospect of controlling an organism via a brain implant became irresistible. José Delgado, a Spanish neurophysiologist at Yale, implanted an electrode into the brain of a fighting bull, in an area “involved in everything from movement to emotion.” Armed with nothing more than a transmitter, he entered a bullring with the beast. As the enraged bull charged toward him, Delgado hit a button, and the bull skidded to a sudden halt. This spectacular demonstration, which was caught on film, helped ensure that his book Physical Control of the Mind: Toward a Psychocivilized Society was a hit when it was published in 1969.

In 2015 … researchers claimed to have implanted electrodes that allowed an autistic teenager to speak for the first time, and ongoing research is focused on, among other things, implants to treat depression. The most well-publicized cases, however, concern the use of electromedicine to repair damaged spinal cords, including by using a device called an oscillating field stimulator (OFS), invented by Richard Borgens, a professor of biomedical engineering at Purdue University.

Work continues. Dr. Min Zhao has shown that during wound healing, the electric field generated by nearby cells holds “veto power” over any growth factor or gene. The cells do what the electric field dictates, regardless of other influences. And two metastudies have demonstrated that stimulation with an electrical current can halve wound healing times. Yet results are inconsistent, in part because nobody really understands how electricity helps wound healing.

Daniel Kehlmann

Susan Neiman reviews:

The Director, by Daniel Kehlmann, translated from the German by Ross Benjamin, Summit, 333 pp., $28.99

From her wide-ranging review I lift just one quote:

The Director shines a light on a few extraordinary people and reveals their behavior during the Third Reich to be painfully ordinary. Kehlmann’s earlier novels are masterful at describing the excuses, equivocations, and lies we are loath to acknowledge, even when they’re fairly harmless: the polite pretense of recognizing an effusive stranger claiming old friendship, the encouraging words a child wants to hear when her parents’ attention is completely distracted. Such scenes can be terribly funny. In The Director the author’s Menschenkenntnis is on full display as he documents the little compromises that led millions of people to nod to fascism.

June 26 Issue

Freedom = Choice?

David A. Bell reviews:

The Age of Choice: A History of Freedom in Modern Life, by Sophia Rosenfeld, Princeton University Press, 462 pp., $37.00

The book is a “history of freedom” that has chapters on, among other things, shopping, dance cards, and market research, and that quotes novels as often as political documents. Unlike most conventional studies of the subject, it casts women as central figures: having a range of choices mattered most to those members of society who had the fewest. Women, Rosenfeld argues, drove the shift that established the equation between freedom and choice, and they drew condemnation in the process. By taking this approach, Rosenfeld presents that equation, which is now mostly taken for granted in the Western world, as a contingent product of a complex historical evolution: “Exposing the constructed nature of that which seems most natural to us in the present is at least a first step in the battle against complacency or the failure to even ask.” … More specifically, she wants to question whether the association of freedom with value-neutral choice-making has been a good thing—for people in general and for women in particular.

In the 18th century,

a time when “freedom” still principally signified freedom from domination by others and few people saw much reason for “maximizing choice-making opportunities.” But in this period a consumer revolution began in Europe and North America, with a rapidly expanding range of goods becoming available to those able to afford them, including coffee, tea, sugar, spices, colorful textiles, printed engravings, books, and ceramics—all made possible by increasingly global trade and the wealth generated by chattel slavery in the Americas. Fashion in clothing and home furnishings, previously the concern of wealthy aristocrats, became a matter of daily life for much more of the population. Shops began to display items for sale in specially designed cases and in windows. Cities widened sidewalks and installed street lighting, making the shops more accessible.

In short, “shopping” was born.

But only in the 19th century did writers begin to applaud the exercise of personal choice.

This important step Rosenfeld associates with battles for women’s rights. Early feminists, especially John Stuart Mill and his companion Harriet Taylor, linked the “subjection of women” to the denial of choice—not just in the political realm but in social and economic ones as well. It was on this foundation that Mill based his more general theory of liberty as something that (in Rosenfeld’s words) “inheres…in the very act of selecting among options…beholden only to an internalized sense of what constitutes the good and right and personally fitting.”

In 1872 in Pontefract, West Yorkshire, the first secret ballot for a parliamentary election took place. Within decades most Western countries adopted this method (as opposed to open, often raucous meetings).

The conflation of freedom with choice—with individual preference—had reached the center of Western political life. As Rosenfeld says in her conclusion, “Choice went from being a benefit of freedom to freedom’s very essence.”

In the twentieth century, Rosenfeld argues, making choices became the focus of even more attention than before. Market researchers took the lead in developing a “science of choice” to determine why consumers chose what they did—the better to manipulate them, of course. Pollsters invented ever more sophisticated methods of gauging public opinion. Economists constructed elaborate models of individual behavior premised on the assumption that the ordinary person—Homo economicus—made rational choices. In much of the Western world, human fulfillment and human liberation themselves came to be associated with the ability to choose. … Sometimes, Rosenfeld notes, “the contemporary obligation of continuous personal choice-making in daily life…has turned into a source of exhaustion, distress, even loneliness and alienation.”

Rosenfeld: “Choice, whether about babies or baubles or beliefs, should be a means, not an end unto itself“ (italics in the original). But, Bell concludes,

there may really be no way to turn back to older visions of freedom, in which what mattered was less the choices one made than the moral ends for which one made them. … [H]ow would a new moral order emerge, and who would get to impose it? … The Age of Choice wants to suggest a way forward out of our present dilemmas. What it has accomplished is to show, with brilliance and originality, just how deep those dilemmas are.

Update - October 1, 2025 : Rosenfeld’s book has been nominated as one of three finalists for the Cundill History Prize, an international prize administered by McGill University. (Source: G&M.)