Toffler in China — The Rise and Fall of Warhorses — How Germany Remade Itself — Christian Supremacy — Phosphorus || Trump and Europe — Lunar Myths and Mysteries — Sex and Christianity — What George Kennan really believed

April 10 Issue

Toffler in China

I recall not wanting to read Alvin Toffler’s Future Shock (1970) when it came out because I shunned (and still do) the hype of crystal ball gazers. But Howard W. French’s essay reveals that the book that came out a decade later, The Third Wave (1980), had a profound influence on Chinese decision makers. China was just then “at a moment of unusual perceptiveness to outside ideas on the part of powerful reformers like Zhao Ziyang” (Premier from 1980 till 1987 and General Secretary of the CPC after that1).

Even Toffler’s language resonated with China’s elite in this post-Mao era:

“Old ways of thinking, old formulas, dogmas, and ideologies, no matter how cherished or useful in the past, no longer fit the facts.”

He foresaw the technological breakthroughs decades ahead as well as their social impacts. Politically, he foresaw that consensus would be shattered due to the “rapid demise of widely held trust in common sources of information“ — a prediction which came through in Western societies.

As well, however, he thought that the decentralization of information (intelligence) would make Big Brother control impossible. China proved him wrong on that. A film like Jialing Zhang’s Total Trust (2023), about China as a surveillance society, shows the opposite of Toffler’s vision of how democracy would be transformed.

And yet, thousands of Shanghai residents’ pushback against China’s Zero Covid policy may well have been instrumental in Xi Jinping doing an about-face.

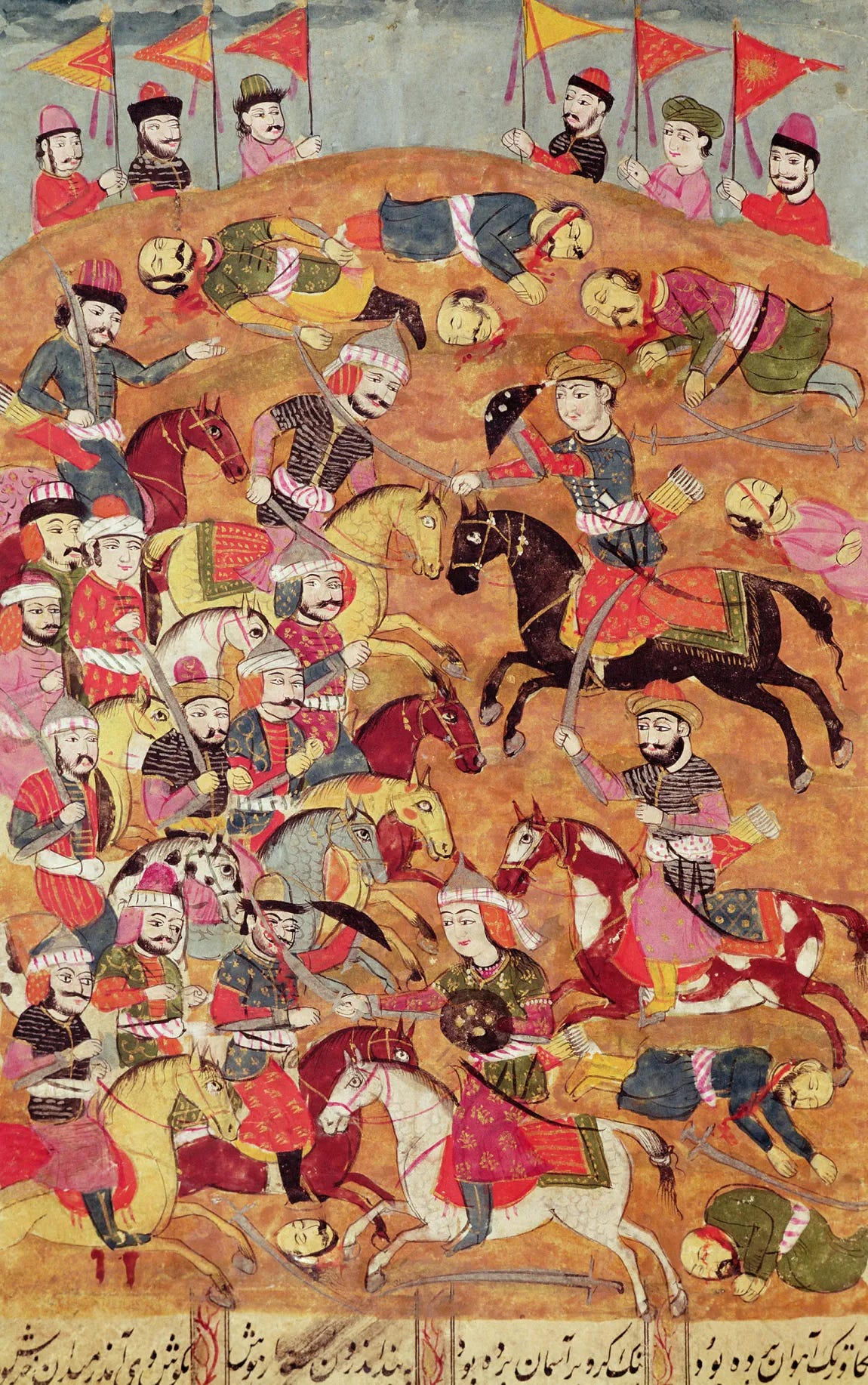

The Rise and Fall of Warhorses

Wendy Doniger reviewed

Raiders, Rulers, and Traders: The Horse and the Rise of Empires, by David Chaffetz, Norton, 424 pp., $32.50

which she finds “[d]espite the erudition of the author … delightfully readable.”

The oldest equine fossils are found in North America, but by the time Cortéz landed there in 1519 there had been no horses on the continent for 12,000 years. All the horses cowboys and Indians rode were descendants from Cortés’s Spanish horses. Millions of years ago the original equines travelled across the landbridge from Alaska to Asia and developed there into three species of Equus: horses, zebras and donkeys. They were domesticated in the steppes around 3000 BCE. (However, a June 2024 report in Nature argues that domestication did not happen until 2200 BCE, although there is evidence of husbandry — for the milk — as far back as 3500 BCE).

Chaffetz notes that “cavalry and empire are like the chicken and the egg”: without cavalry you couldn’t have an empire, but you needed an empire to be able to support the great number of horses needed for a cavalry. … With cavalry, even small nations could attack and defeat powerful states, but the emergence of great settled empires was a function of the amount and quality of horses they could mobilize.

On the steppes everyone, including women, rode a horse, but in Western Europe not more than 1 or 2 percent of the population did — the aristocrats. The increasingly critical attitude towards aristocracy can be traced through the shifting meaning of the word “cavalier” — from a noun meaning a gentleman or skilled horseman in the mid-1500s to an adjective a hundred years later meaning highhanded, arrogant, etc.

Once the Industrial Revolution took hold, “[a]fter four thousand years, horses ceased to be a strategic asset in human life.” “The highest economic value of horses came to lie in racing.”

How Germany Remade Itself

Yet another article on post-war Germany.2 Christian Caryl reviewed

After the Nazis: The Story of Culture in West Germany, by Michael H. Kater, Yale University Press, 517 pp., $35.00

Out of the Darkness: The Germans, 1942–2022, by Frank Trentmann, Knopf, 784 pp., $50.00

Both authors show that the post-war outcome of a liberal democratic Germany was by no means assured. Trentmann gives a nuanced interpretation of the role of Konrad Adenauer (Chancellor from 1949 till 1963).

East and West Germany responded very differently to dealing with its immediate past:

The East, deeming itself free of any responsibility for the Nazi era, promoted a version of history in which Communists were the Nazis’ main victims and that gave little acknowledgment to the Holocaust. In its early years the West lurched between confronting the past and effacing it. Even so, the purge of the highest-ranking Nazis on both sides of the divide in the years immediately after the war did at least provide space for new elites—some of them former political prisoners or returning émigrés—to establish themselves.

Factoid:

Modern scholarship concludes that at least 200,000 people were directly involved in implementing the Holocaust, and that number doesn’t include the many soldiers of the regular armed forces who also took part in genocidal actions.

Kater chronicles “how culture aided Germans’ gradual acknowledgment of these burdens of the past.”

Both Trentmann and Kater demonstrate that Germany’s progress toward today’s emphatically liberal democracy was often bumpy and ambivalent. (The Federal Republic only abolished long-established laws against homosexuality in 1969.)

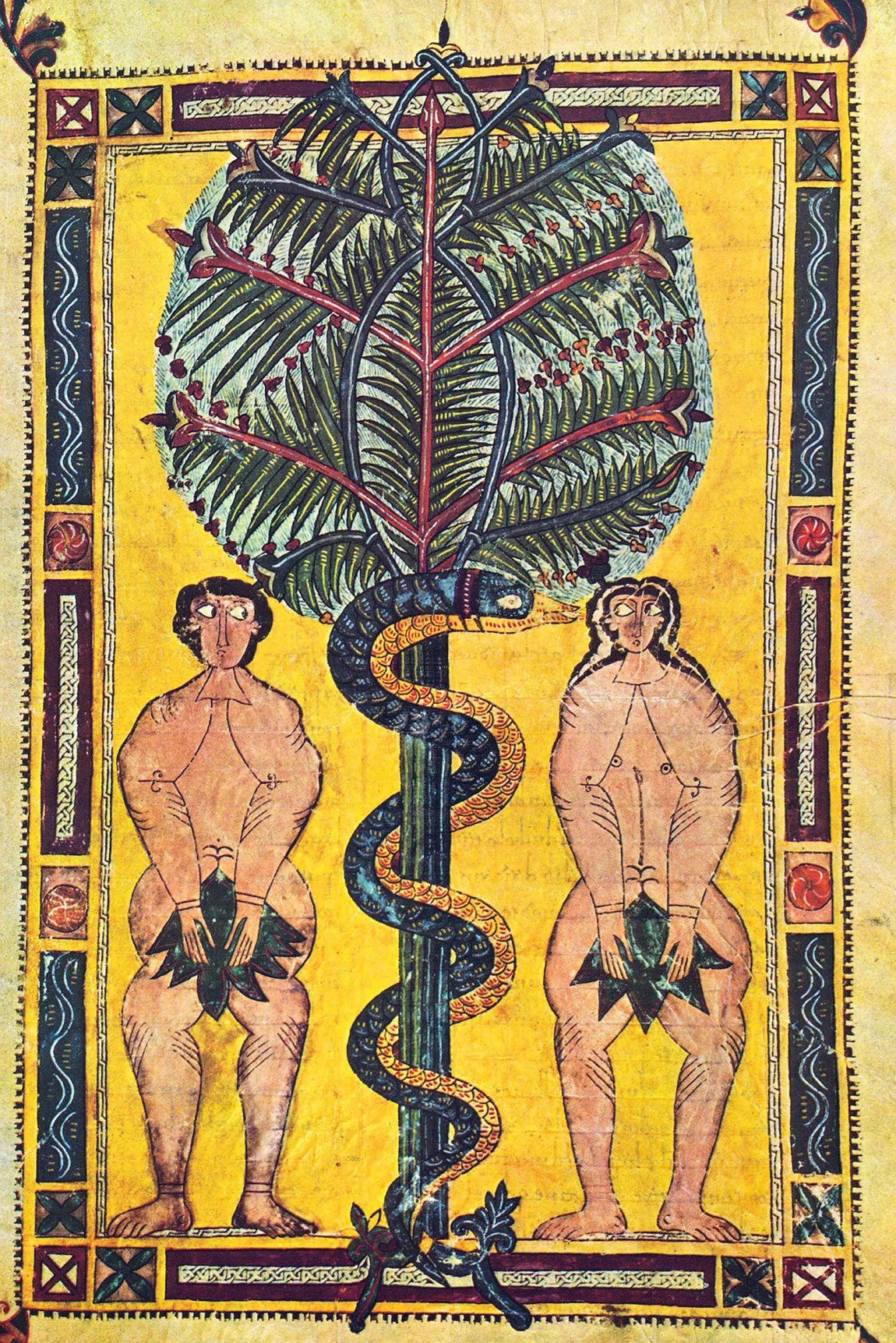

Christian Supremacy

Under the title Christian Hair Miri Rubin reviewed

Christian Supremacy: Reckoning with the Roots of Antisemitism and Racism, by Magda Teter, Princeton University Press, 389 pp., $35.00; $24.95 (paper)

At the heart of Christian historical understanding was the idea of supersession. The idea was this: the new faith would replace Judaism, thus establishing its own superiority. This religious, political, and ethical concept was translated into legal and administrative procedures over the centuries, thereby shaping relations between Christians and Jews. Supersession has therefore been much discussed as the conceptual bedrock of anti-Judaism. Now Magda Teter’s Christian Supremacy: Reckoning with the Roots of Antisemitism and Racism argues that supersession offered foundations for white supremacy, too.

Paul’s theology crystallized how the new superseded the old. Emperor Constantine wedded his empire to Christianity. Augustine “created the theological underpinnings for a Christian empire.” Jews who did not convert were consigned to be subservient to the Christian state as protected inferiors.

Medieval rulers from Hungary to England developed a uniquely direct lord–servant relationship with Jews out of the combined legacies of theology and law.

In the 12th century

it became common in Western imagery to depict Jews as antagonistic to Christ, using a distinctive nose that set them apart from Christian believers at scenes of the Crucifixion (see illustration, middle figure on the left).

But over the centuries attitudes hardened. Franciscan preachers claimed Jews were deicides.

Rulers were torn between the benefit of working with Jews who were dependent, expert, and loyal and the pressure exerted by religious authorities and preachers who wished them degraded or gone.

The 1492 expulsions in Spain affected both Jews and Muslims. Teter argues that Christian supremacy laid the foundation for racism. Factoid:

The Castilian word raça, meaning a defect in a gem or piece of cloth, came to describe an immutable human quality.

In North America Jews and Blacks became the victims of racism.

Rubin goes on to reflect on the similarity in aspirations of both Jews and Blacks:

The Russian pogroms of the 1880s and the experience of reporting on the Dreyfus affair from Paris led Theodor Herzl to imagine an “old new” state for Jews where they could flourish and feel safe.

[Marcus] Garvey also believed in such self-assertion, as he put it succinctly in 1919:

“We may make progress in America, the West Indies and other foreign countries, but there will never be any real lasting progress until the Negro makes of Africa a strong and powerful Republic to lend protection to the success we make in foreign lands.”

Comment: It is surprising that Rubin or the book do not extend the analogy to racism aimed at Native Indians/Arabs/Muslims/any non-white immigrants.

Phosphorus

In Planet Ooze, Jonathan Mingle reviewed

The Devil’s Element: Phosphorus and a World Out of Balance, by Dan Egan, Norton, 228 pp., $30.00; $18.99 (paper)

The Planetary Boundary we overshoot the most is nutrient flows (“modification of biogeochemical flows” in PB parlance) — that is,

the spillage of nitrogen and phosphorus from our agricultural and industrial processes into our ecosystems. Both nitrogen and phosphorus are “limiting factors” essential for plant growth. For billions of years, the rates at which those two elements cycled through the world’s food chains were relatively stable. Then the twentieth century brought industrial-scale phosphorus mining and scientific breakthroughs that unlocked the atmosphere’s nitrogen for fertilizer manufacturing.

…

Without steady supplies of phosphorus, there can be no mass production of corn, soy, wheat, vegetables—all the staples that feed eight billion people and counting. One ton of phosphate is needed to produce 130 tons of grain. Egan quotes Isaac Asimov’s blunt assessment in 1974: “Life can multiply until all the phosphorus is gone and then there is an inexorable halt which nothing can prevent.”

…

…the primary sources for modern agriculture are deposits of ancient sedimentary phosphate rock scattered around the globe, from central Florida to Morocco to China. … Morocco holds more than 70 percent of the world’s phosphate rock reserves. Its state-owned fertilizer producer accounts for a fifth of the country’s total export revenue and is the biggest employer.

…

Estimates for the life span of known global phosphate reserves range from a few decades to four hundred years, depending on the rate at which we continue to let it spill into rivers, seas, and lakes.

Dan Egan’s first book was The Death and Life of the Great Lakes [2018].

Egan doesn’t put it this way, but the implicit question posed by both of his books is this: Can our civilization mature quickly enough to stop shitting where we eat? … One way of thinking about phosphorus: it’s the clearest, most damning indicator that our civilization has yet to reach adulthood.

Remedies, at least in the US, are likely to become harder to get to, in the wake of the Supreme Court’s Chevron decision.3

Just as the dashboard lights are blinking brighter and faster, the Court’s conservative majority has locked the steering wheel and cut one of the brake lines.

…

We can avoid Asimov’s dead end, if we choose, by making our food systems more efficient and getting better at capturing and recycling phosphorus from waste and effluent. Improved farming techniques such as planting cover crops and integrating livestock and crop production can reduce the need for chemical fertilizers, and new technologies can help farmers time and target their application more precisely. Shifting our diets away from meat and dairy and toward, say, legumes would also reduce fertilizer use for the growth of animal feed crops.

April 24 Issue

Trump and Europe

Fintan O’Toole’s essay, Shredding the Postwas Order, datelined March 26, reviews the Trump regime’s position towards Poland and how it has changed since Trump’s laudatory remarks during a speech in Warsaw in 2017. (Poles give the US a higher rating — 86% favourable view — than any of 34 countries Pew surveyed last year.) More generally, he traces Trump’s attitude vis-à-vis the European Union which he sees as a greater enemy than Russia and on a par with China. This sense was there in his first term but he is now being egged on by those around him. And it’s not just trade: Distorted ideas of masculinity held by him and his acolytes also play a role.

To answer the question of what happened to turn Trump’s lavish praise for Poland in 2017 into his henchmen’s supercilious sneering of 2025: three things have changed. They are Trump’s impeachment in 2019 over his attempted shakedown of Zelensky (as well as the Mueller report earlier that year into Russia’s interference in the 2016 US election); a much more aggressive desire to interfere in European domestic politics in support of far-right and neofascist parties; and Trump’s new alliance with Big Tech.

Vance’s speech in Munich last February features large in the essay.

O’Toole asserts that almost all European leaders know “that the postwar period of European history has now definitely ended.”

Lunar Myths and Mysteries

Jenny Uglow reviewed:

Lunar: A History of the Moon in Myths, Maps, and Matter, edited by Matthew Shindell, with a foreword by Dava Sobel, University of Chicago Press, 256 pp., $65.00

Our Moon: How Earth’s Celestial Companion Transformed the Planet, Guided Evolution, and Made Us Who We Are, by Rebecca Boyle, Random House, 313 pp., $28.99

She writes:

…the two books could not be more different. Our Moon by Rebecca Boyle, a contributing editor at Scientific American, is a compact, sparkling, fact-filled work of popular science. By contrast, Lunar, edited by Matthew Shindell, a curator at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, and full of astonishing illustrations, is a large quarto volume so weighty that one would need a strong coffee table to display it.

Lunar is

effectively an atlas, containing forty-four maps of the moon’s surface that are accompanied by photographs from satellites and lunar missions and interspersed with short, vivid essays, crisply detached in tone, on everything from myth to movies.

Something I didn’t know:

The moon stabilizes the Earth’s tilt that gives us our seasons; without it, Boyle writes, “gravitational interference from Jupiter would push Earth around like a playground bully.”

And this:

In the third century BCE Aristarchus of Samos …, … by calculating the angles between Earth, the moon, and the sun, … became the first to propose that Earth revolves around the sun in a year.

Sex and Christianity

Under the title Vexed by Sex Erin Maglaque reviewed:

Lower Than the Angels: A History of Sex and Christianity, by Diarmaid MacCulloch, Viking, 660 pp., $40.00

Diarmaid MacCulloch is emeritus professor of church history at Oxford. “Lower Than the Angels is the sexier counterpart to his award-winning A History of Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (2009).“

MacCulloch argues and amply demonstrates that there is not and never has been a single Christian theology of sex.

There were no finer theorists of erotic fantasy, of what went on in the back of the heart, than medieval mystic women. … The Cistercian Ida of Gorsleeuw, in Belgium, for example, was idly praying matins when she felt Christ “sending forth his heavenly hand through the key hole.” It isn’t until we encounter the full lyric in the Song of Songs—“My beloved put his hand through the keyhole, and my womb was moved at his touch”—that we realize which hole, exactly, Ida was talking about. Another Belgian mystic Ida (of Nivelles) was visited by Christ; he came to her with his lips smeared in thick white liquid that he dripped into her mouth, sharing with her “bountifully…this tastiest of honeycombs.” This image was also borrowed from the Song of Songs: “Thy lips, O my spouse, drip as the honeycomb.” These women were Christ’s lovers, the bride to his bridegroom.

Hadewijch, the Flemish Beguine,

wrote inventive poems about Christ as her lover. … her lyrics sound like a description of an orgasm: “He came himself to me, took me entirely in his arms, and pressed me to him…so I was outwardly satisfied and fully transported.” Hadewijch begins to dissolve: “I could no longer distinguish him within me.”

If the long history of Christianity and sexuality offers a detailed canon of fantasies, there is plenty of shame and sin, too—sodomy, adultery, self-pleasure.

Between the Roman and the Jewish traditions, monogamous marriage was the dominant cultural practice of the Mediterranean world before Christ.

It wasn’t until Pope Gregory VII’s reforms of the western Church in the eleventh century that the theology of marriage and celibacy changed. Total clerical celibacy became the norm.

During the Reformation the ideal of clerical celibacy fractured again. Luther celebrated the family, married sexuality, and children, both for the laity and for the clergy. Protestant priests took wives. For Catholics this was a point of major contention, and clerical celibacy had to be defended as an almost supernatural accomplishment. … Pope Sixtus V brought back the death penalty for adulterers in Rome in 1586.

For much of the past two thousand years, sexual images and fantasies came not from pornography but from scripture. Desire found its most powerful expressions in celibacy, in communal religious life, in the radical experiments of ascetics and utopians. What we consider to be erotic today seems so narrow in comparison, so hopelessly trammeled by the twin forces of pornography and marriage. The history of sex and Christianity suggests that desire is not only some natural impulse but substantially a creation of culture—that is, the stuff of the imagination.

What George Kennan really believed

Under the title The Enigma of George Kennan, Benjamin Nathans reviewed

Kennan: A Life Between Worlds, by Frank Costigliola, Princeton University Press, 624 pp., $39.95; $24.95 (paper)

George F. Kennan [1904-2005], the subject of half a dozen biographies, is best known as the architect of America’s grand strategy of “containment” in the cold war against the Soviet Union. He is almost as well known for being the fiercest critic of the way that strategy was overmilitarized by every American administration from Harry Truman through Ronald Reagan, with partial clemency for Richard Nixon and his secretary of state Henry Kissinger because of their pursuit of détente with Moscow.

Kennan’s most consequential statements came early in his career: the “Long Telegram” (sent from Moscow to the State Department in February 1946) and “The Sources of Soviet Conduct” (published under the byline “X” in Foreign Affairs in July 1947). Both texts attempted to explain the sudden souring of relations between the US and the USSR, after their cooperation in defeating Nazi Germany, as a function of the Bolsheviks’ peculiar blend of traditional Russian insecurity and Marxist-Leninist messianism.

John Lewis Gaddis’ authorized biography (an “encomium”), George F. Kennan: An American Life (2011), has not aged well. As this new biography shows, Kennan himself “doubted not just Gaddis’s rosy assessment of containment’s legacy but whether that legacy was worth striving for in the first place.“

More than any previous biographer, Costigliola mines Kennan’s work for its profound ambivalence toward both democracy and capitalism, if by the latter we understand rampant industrialization and the preeminence of market forces in modern life.

Costigliola’s biography leaves little doubt that Kennan’s thinking remained remarkably the same and that its most durable elements were precisely his skepticism vis-à-vis industrial capitalism and what he called “the fetish of democracy.” These were not quirks, as they appear to be in Gaddis’s admiring portrait; they were fundaments of his worldview from start to finish.

The greatest enigma about Kennan was not his relationship to the doctrine of containment but his relationship to Russia. … The enduring fantasy of an uninhibited Russian version of himself suggests a certain loathing for the American original. … For all [his] psychic investment [in Russia], he seems not to have had a single close Russian friend.

Kennan wrote in his diary in 2000 that Gaddis “had no idea of what was really at stake” in the “lone battle I was waging…against the almost total militarization of Western policy toward Russia—one which, had my efforts been successful, would have, or could have, obviated the vast expenses, dangers, and distortions of outlook of the ensuing Cold War.”

He lost power in 1989 when he supported the student protests at Tiananmen Square.

Ref. https://erwindreessen.substack.com/i/146346447/us-supreme-court-going-rogue: “Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo [2024]: Overturns the 40-year old “Chevron” doctrine (decided back then 6-0) which held that, in case of ambiguity, courts must show deference to the administrative agency.“